It’s no secret that campaigns want to control public discourse. Political professionals admit it, and while the democratizing potential of the internet is a refrain we often hear, persuasive arguments that we are merely having the wool pulled over our eyes while we are controlled in ever-more nefarious ways have been pretty compelling (see: Phil Howard, Eli Pariser, Matt Hindman). Despite this seemingly obvious truth, in many ways, the 2010 midterm elections marked a change in campaigns’ ability to control messages. Across the nation, communications offices still attempted to tamp down on messages that are misaligned with their own, and publicized those they preferred, but their ability to do so—or at least to do so overtly—was diminishing. While digital technologies are certainly used to control which potential voters get what messages, digital media are also confounding the traditional stranglehold campaigns have had on the information that circulates about a candidate.

Ultimately, campaigns used social media tools in ways that made a significant move away from traditional, overt control, which involves the direct censorship of comments. Rather than relinquishing control entirely, they moved toward new methods of control that have varying levels of openness. Often, when shifts in strategy occur, they are just that: strategic. But the tactics and strategies deployed by campaigns in 2010 tell a more interesting story. When traditional forms of control such as censoring or deleting public commentary became dangerous, rather than slip into a slightly less visible form of control, campaigns—due not to their desires, but because of the consequences of their technical choices for media platforms and their shifting organizational structure—found themselves needing to deploy new and different forms of control.

Most commonly, campaigns realized that overt control was not as productive in a digital environment due to the ability for opponents to digitally document, reproduce, and circulate any missteps:

As this became less strategically beneficial, campaigns moved away from traditional, overt forms of control.

In doing so, they discreet control, which involves disabling some interactive features of digital media and enabling backend controls that allow for control without having to publicly erase content or completely prohibit interaction with citizens. While this made strategic sense to campaigns, it became a more interesting story after the 2010 elections, when platforms like Facebook made changes to their user experience

Campaigns, because they are accustomed to using publicly-available tools, are at the mercy of the affordances provided by these tools. While the 2010 version of Facebook allowed for more severe limiting of politicians pages on the backend—controlling who can post and where they can do so—they lost some of these capabilities after the UX change.

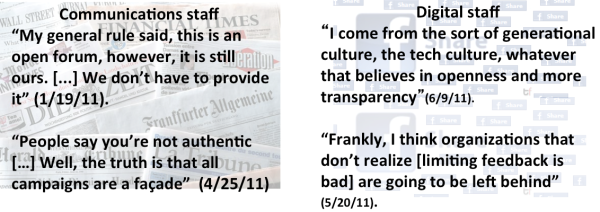

Even beyond technological shifts, campaigns’ available means of control were also colored by the organizational changes that began to hit campaigns in 2010, with the rise of digital media strategy as in-house campaign staffers. Occurring in races as technically advanced as Obama’s 2012 race, the cultural differences between communications and digital teams often had ripple effects. During decisions about how much control should be wielded do arise, organizational divides usually occur along professional fault lines; those with traditional communications or press backgrounds on one side, and those who have come up as digital specialists on the other.

As a result of this push to become more deeply dedicated to openness, campaigns began to engage in indirect control which involves allowing for the actions associated with deliberation—spaces to voice opinions, disagree, and engage in reciprocal communication—while also exerting great power in setting an agenda that is of strategic benefit to the campaign regardless of topics’ importance to the public. Far from a strategy that the higher-ups in most campaigns wanted to deploy, the move toward more open interaction with citizens was part of of a cultural shift in campaigns that was an unforeseen consequence of organizational changes.

As a result of this push to become more deeply dedicated to openness, campaigns began to engage in indirect control which involves allowing for the actions associated with deliberation—spaces to voice opinions, disagree, and engage in reciprocal communication—while also exerting great power in setting an agenda that is of strategic benefit to the campaign regardless of topics’ importance to the public. Far from a strategy that the higher-ups in most campaigns wanted to deploy, the move toward more open interaction with citizens was part of of a cultural shift in campaigns that was an unforeseen consequence of organizational changes.