While organizations like the Knight Foundation have begun to chart the field of civic tools, the designations are often assumed to be apolitical and merely representational of the genres of tools that exist in the space. But as the area of civic media begins to get more attention and such tools are increasingly the subject of (warranted!) criticism from academics (myself and Eric Gordon, Dan Kreiss, Jenny Stromer-Galley, and Jim Katz have all written about how pseudo-engaging tools are being adopted in campaigns and in governance).

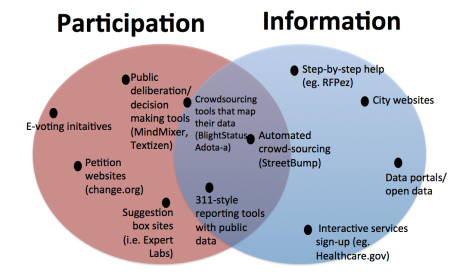

As governments adopt ICTs as a way to improve service delivery and meet the needs of their communities, the very use of such tools also implicitly—and sometimes explicitly—sheds light on the democratic values encouraged or emphasized. For instance, a tool designed with the goal of streamlining intra-governmental communications or practices values efficiency; open data initiatives value transparency and an informed citizenry; calls for online town halls value deliberative practice and a governing institution that solicits feedback from its citizens. Although these projects share broad goals of improving governance, information-related goals differ from those that are engagement-focused. As a result, a categorization scheme that attends to this information/participation continuum helps better illuminate the democratic norms upheld and furthered by such tools. Even just looking at emerging media in a civic, non-campaign setting, the landscape of tools begins to look like: